Black History Month: Insight into the lives and scientific inventions of material marvels

This article was originally published on 27/09/2019 by Shardell Joseph for IOM3’s Materials World website for Black History Month 2019.

Out of slavery, inequality, and racial adversity, black engineers have made significant contributions to technological advancements and material marvels throughout history. Shardell Joseph looks at the obstacles that inventors faced, and their achievements in science.

Standing on the shoulders of giants – a concept traced back to the 12th Century and famously used by Sir Isaac Newton – expresses how discovering the truth or making progress must be done by building on previous work. For people born into oppression and facing racial adversity, however, these metaphorical shoulders are often out of reach, and the step up the ladder is not as accessible.

The relationship between racial and economic inequality and individual mobility among African Americans in the USA has been studied – often finding that as a response to racial discrimination and limitations, many individuals failed to develop a strong academic orientation. Oppression and opportunity are contradictory in nature, and throughout history the limitations imposed on ethnic minorities within many western societies have undeniably halted potential innovation and progress.

Despite the unimaginable adversities and obstacles encountered based on race, whether overcoming slavery, ethnicity bias or gender limitations, there have been momentous contributions made by unrecognised black scientists who invented designs and technologies that disrupted industries with long-lasting effects.

Railway coupling

Invented by Andrew Jackson Beard (1849-1921) in 1887, the Jenny coupler was the first fully automatic railroad car coupler. Widely adopted in the USA, the Jenny coupler made huge improvements to railway safety, and US Congress later passed the Federal Safety Appliance Act, which made it illegal to operate any railroad car without automatic couplers.

Beard successfully revolutionised railroad safety, but his origins were slavery. Hailing from Woodland, Alabama, Beard was born at a time shortly before slavery ended. Emancipated at the age of 15, Beard’s elaborate career path – going from farmer, to carpenter, blacksmith, railroad worker, and then businessman – led him to become an important inventor for the railroad industry. Without the means of a standard education, Beard utilised the knowledge from his fields of work to make inventions that would later benefit many industries.

Growing apples as a farmer for five years, Beard then built a flourmill in Hardwicks, Alabama. Taking inspiration from his agricultural experience, Beard filed his first patent in 1881 for improved design on the double plough, and he sold the rights in 1884. In 1887, Beard filed a patent for a second plough – a design that allowed the pitch of the blades of ploughs or cultivators to be adjusted for better use.

Beard filed two patents for rotary steam engine designs, which were granted in 1890. After losing his leg in a car coupling accident, Beard later made significant improvements to railroad car couplers, specifically the knuckle coupler, which was patented in 1897. Beard sold his rights to the patent for US$500,000, the equivalent of US$1.5mln today. In total, Beard was granted three car-coupling patents.

Used as a mechanism to connect rolling stock in trains, the railroad car coupler became an imperative component to railroad technology. Originating from the link and pin design, which consisted of a tube-like component with an oblong link, the manual use of couplers required a railroad worker to stand between the cars as they came together, guiding the link into the coupler pocket.

The Janney coupler, also known as the knuckler coupler, was a semi-automatic design patented by US confederate soldier Eli H Janney in 1873. Consisting of a hook and catch, the device allowed car coupling without the use of link and pin, which was considered to be extremely dangerous.

Then came the Jenny coupler which improved upon this design, making the coupler fully automatic. The Jenny automatically joined cars, which allowed them to bump into each other, described by Beard as ‘horizontal jaws’ that engage each other to connect to cars.

Beard was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2006 in recognition of his revolutionary Jenny coupler.

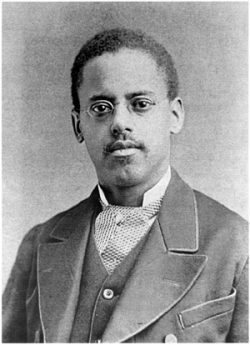

The carbon light bulb

Improving the original works of Thomas Edison, Lewis Howard Latimer (1848-1928) invented a light bulb with a carbon filament incorporated into it, globally used to this day. The improved filament within the bulb was invented in an effort to create a longer lasting bulb.

Considered one of the 10 most important black inventors of all time, Latimer became known for the sheer magnitude of his, arguably most important, discovery. Latimer was based in Massachusetts after his parents migrated from Virginia in 1842 to escape their slave owners. His father, George Latimer, become notorious when his owner recaptured him, but abolition supporters took his case to Massachusetts Supreme Court and bought him his freedom.

Lacking financial means, Lewis Latimer’s childhood consisted of restricted access to education, even though he attended grammar school and was an excellent student, as he was expected to work and earn money for his family. At the age of 15, Lewis Latimer joined the US Navy, serving as a landsman on the USS Massasoit. He later received an honourable discharge in 1865 when the Civil War ended.

Latimer searched for work throughout Boston, and eventually found employment as an office boy with patent law firm, Crosby and Gould. There, Latimer met Alexander Graham Bell who, eager to beat his competition to gaining patent rights, hired him to draw the plans for a new invention, the telephone. By working with him late at night, Latimer was able to provide Bell with the blueprints and expertise in submitting applications that allowed him to file his telephone patent on 14 February, 1876, just a few hours earlier than Bell’s rival inventor.

In 1880, Latimer began work as a mechanical draftsman for Hiram Maxim, an inventor and founder of the US Electric Lighting Company in Brooklyn, New York. In his new job, Latimer was given the opportunity to get familiar with the field of electric incandescent lighting. In 1881, along with Joseph Nichols, Latimer invented a light bulb with a carbon filament – an improvement on Thomas Edison’s original paper filament, which would burn out quickly – and sold the patent to the US Electric Lighting Company the same year.

The incandescent light bulb has had incarnations prior to Joseph Swan and Thomas Edison, but it was the combination of the incandescent material that achieved a higher vacuum and higher resistance, which made Edison’s and Swan’s contributions more economically viable. It consisted of a wire filament heated to such a high temperature that it would glow a visible light.

As part of Edison’s elite research team, named Edison’s Pioneers, Latimer improved Edison’s light bulb by incorporating carbon. Edison’s prototype was lit by a glowing, electrified filament made of paper, which unfortunately burnt out rather quickly. Latimer created a new design with a filament made of carbon that was much more durable. Working within the research team of the original creator, Latimer’s contribution to the carbon light bulb has often been credited to Edison.

Although today’s light bulbs use filaments of tungsten, which lasts even longer, Latimer should always be remembered for making the widespread use of electric light possible, in public and at home. After he sold the patent Incandescent electric light bulb with carbon filament to the US Electric Lighting Company in 1881, Latimer went on to patent a process for efficiently manufacturing the carbon filament (1882) and developed the now familiar threaded socket – though his was wooden – for his improved bulb.

Parallel to his innovations, Latimer had a passion for social justice. This was evident in his book Incandescent electric lighting: A practical description of the Edison system, published in 1890, which demonstrated an understanding of how the new technology could bring electricity to those who previously could not afford it. On the electric lamp he wrote, ‘Like the light of the sun, it beautifies all things on which it shines, and is no less welcome in the palace than in the humblest home’.

In a letter he wrote in 1895 in support of the National Conference of Colored Men, Latimer wrote, ‘I have faith to believe that the nation will respond to our plea for equality before the law, security under the law, and an opportunity, by and through maintenance of the law, to enjoy with our fellow citizens of all races and complexions the blessings guaranteed us under

the constitution’.

The Laserphaco probe

‘Sexism, racism and relative poverty were the obstacles I faced as a young girl growing up in Harlem,’ Dr Patricia Bath (1942-2019) said in an interview. As the first woman ophthalmologist to be appointed to the faculty of the University of California at Los Angeles School of Medicine Jules Stein Eye Institute, Bath had discovered and invented a device and technique for cataract surgery known as Laserphaco in 1986.

Bath’s dedication to a life in medicine began in childhood, when she was first heard about Dr Albert Schweitzer’s service to lepers in the Democratic Republic of Congo. After excelling in her studies in high school and university, and earning awards for scientific research as early as age 16, Bath embarked on a career in medicine. She attributed this to her mother, who she said scrubbed floors so she could access medical school.

‘There were no women physicians I knew of and surgery was a male-dominated profession. No high schools existed in Harlem, a predominantly black community – additionally, blacks were excluded from numerous medical schools and medical societies, and my family did not possess the funds to send me to medical school,’ Bath said. Bath received her medical degree from Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, DC, interned at Harlem Hospital from 1968-1969, and completed a fellowship in ophthalmology at Columbia University from 1969-1970.

As a young intern shuttling between Harlem Hospital and Columbia University, Bath was quick to observe that, at the eye clinic in Harlem, half of the patients were blind or visually impaired. In contrast, there were very few obviously blind patients at the Columbia clinic. This observation led her to conduct a retrospective epidemiological study, which documented that blindness among black people was double that experienced among white people.

She reached the conclusion that the high prevalence of blindness among black people was due to lack of access to ophthalmic care. As a result, she proposed a new discipline, known as community ophthalmology, which is now operative worldwide. The discipline combines aspects of public health, community medicine, and clinical ophthalmology to offer primary care to underserved populations.

Her interests and research in restoring sight led her to invent and patent a technology that changed the course of cataract treatment. Bath’s invention of the Cataract Laserphaco Probe was designed to use laser technology to painlessly eliminate cataracts. This quick method soon replaced previous ones within the medical field and went on to revolutionise eye surgery.

The Laserphaco Probe uses a system of lasers, suction, and irrigation to remove the affected lens and replace it with an artificial one that will not deteriorate over time. The probe consists of an optical laser fibre surrounded by the irrigation and aspiration suction tubes. The laser probe can be inserted in a 1mm incision in the eye. The laser energy vaporises, or phacoblates, the cataract and lens matter within a few minutes. The decomposed one is extracted when liquid supplied by the irrigation line washes through and is ducked out through the aspiration tube, and a replacement lens in inserted.

In 1993, Bath retired from UCLA Medical Center and was appointed to the honorary medical staff. After that, she advocated for telemedicine, the use of electronic communication to provide medical services to remote areas where health care is limited. She has held positions in telemedicine at Howard University and St George’s University in Grenada.

Paving the way for future innovation

Showcasing just a tiny drop in a huge pool of talent, black engineers and scientists have made important and deeply impactful advances, relentlessly working against obstacles they faced, both in recent and older history.

Some have become famous due to events celebrating achievements made by individuals specifically within the black community, but many more have gone unrecognised or underappreciated for their contributions to scientific and technological advancements due to political and social climates.

Celebrating the achievements of the past not only gives inventors their deserved recognition, but also creates an effective dialogue as to why the scientific community should support and implement greater diversity inclusion in the future.